Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only cost 10% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s a win for patients and insurers. But for the companies making those drugs? It’s a race to the bottom. In 2025, the U.S. generic drug market brought in just $35 billion-down 6.1% over five years. Meanwhile, companies like Teva lost $174 million last year. How can a business survive when every pill you sell earns pennies?

The commodity trap: why simple generics are dying

The easiest path into generic manufacturing used to be copying old, off-patent pills-like metformin, lisinopril, or amoxicillin. Easy to make. Easy to get approved. But now, dozens of companies make the same drug. The result? Price wars. One manufacturer cuts the price by 5%. Another drops it by 10%. Soon, the profit margin is below 20%. Some are down to 5%.This isn’t just bad business-it’s dangerous. When margins shrink too far, companies stop making certain drugs. That’s when shortages happen. In 2024, the FDA recorded over 300 drug shortages, many of them generic antibiotics or critical heart medications. Why? Because no one could make money producing them anymore.

The cost to get a generic drug approved? Around $2.6 million per application. The factory to make it? At least $100 million to meet FDA standards. If you’re selling a 30-day supply of generic atenolol for $4, you’re not going to break even unless you sell millions of units every month. And even then, you’re barely surviving.

Complex generics: the new profit engine

Not all generics are created equal. Some drugs are hard to copy. They need special formulations. They require precise delivery systems. They might be injectables, inhalers, or patches that release medicine slowly over time. These are called complex generics.These aren’t easy to make. It takes advanced chemistry. Specialized equipment. Years of testing. And because there are fewer competitors, the pricing doesn’t crash. Companies like Teva and Viatris are pouring money into these. Teva’s revenue grew 4% in 2024-not because of cheap pills, but because of drugs like Austedo XR for movement disorders and lenalidomide for multiple myeloma. These aren’t just copies. They’re improved versions with better patient outcomes.

Profit margins on complex generics? They can hit 40-50%. That’s the difference between losing money and staying in business. It’s why the FDA approved fewer complex generics in 2022 than simple ones-but they accounted for nearly half of all generic savings. The market rewards those who can solve hard problems, not just copy labels.

Contract manufacturing: selling your factory, not your pills

Another way out of the commodity trap? Stop selling drugs altogether. Start selling your factory.Contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) don’t own the brand. They don’t market the drug. They just make it-for other companies. Branded pharma firms outsource production to save money. Generic makers with extra capacity lease it out. This segment is growing fast: from $52 billion in 2024 to nearly $91 billion by 2030.

Egis Pharmaceuticals launched Egis Pharma Services in 2023 to do exactly this. They’re not competing in the price war for generic metformin. They’re making API (active pharmaceutical ingredients) for companies that need it. Same factory. Same equipment. Same FDA inspections. But now they’re paid for expertise, not volume.

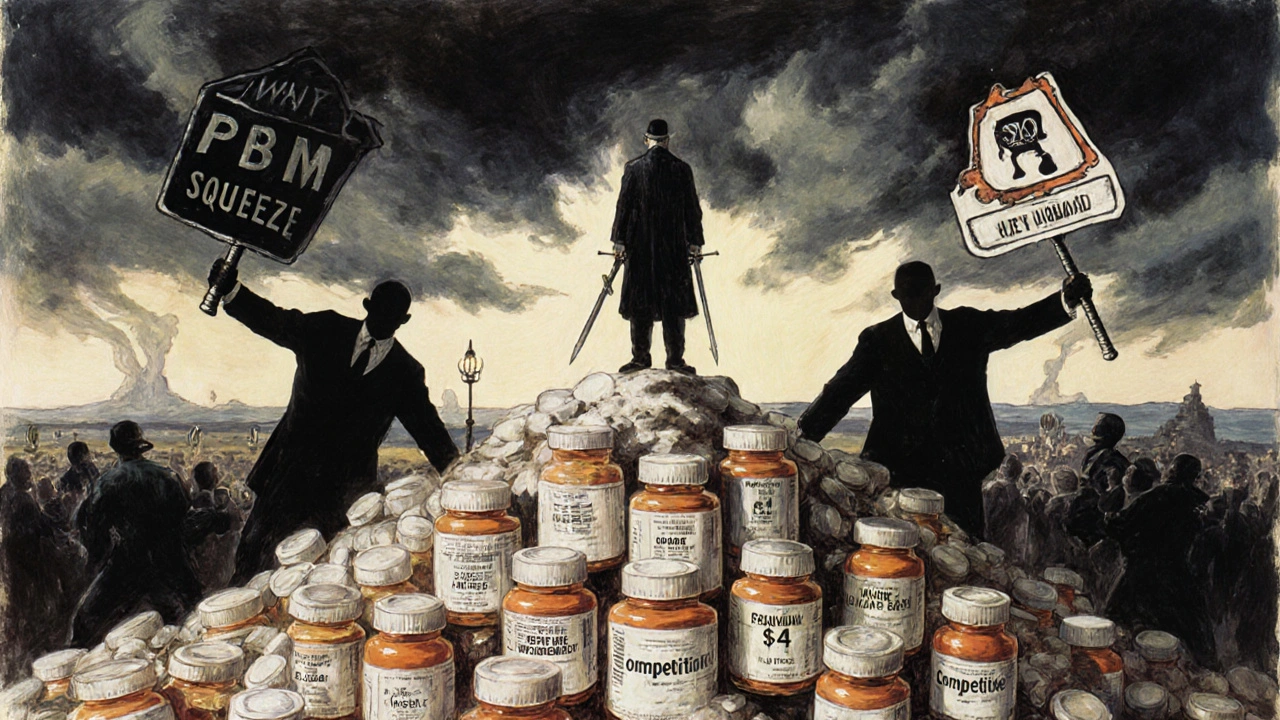

This model is more stable. Contracts last years. Pricing is negotiated. There’s less volatility. And because you’re not fighting for shelf space in a pharmacy, you’re not at the mercy of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) who squeeze prices even further.

Why consolidation is inevitable

The cost of entry is too high. The margins are too thin. The risks are too big. So companies are merging.In 2020, Mylan and Upjohn merged to form Viatris. In 2024, Viatris sold off its biosimilars unit and its over-the-counter division. Why? To focus on what still makes money: complex generics and stable contract manufacturing. Teva, once the world’s largest generic maker, sold its European retail pharmacy chain and its U.S. consumer health business. They’re shedding anything that doesn’t fit their new strategy.

Consolidation isn’t just about size. It’s about survival. Smaller players who try to compete head-on in commodity generics? They fail. A 2024 McKinsey analysis found that over 65% of new entrants focusing only on simple generics shut down within two years. The FDA approval process alone takes 18-24 months. By then, the price has dropped again. The market moves too fast for small, underfunded players.

The global picture: where the money is

The U.S. isn’t the whole story. In Europe, pricing rules are different. Governments set reimbursement rates, but they’re not as aggressive as U.S. PBMs. That means better margins for manufacturers. In India and China, production costs are lower, and domestic demand is rising. But there’s a catch: regulatory uncertainty, currency swings, and IP risks.North America still leads in contract manufacturing revenue, but Asia-Pacific is growing fastest. Countries like South Korea and Singapore are investing heavily in high-quality manufacturing infrastructure. They’re attracting global pharma companies looking for reliable partners outside the U.S. and Europe.

By 2033, the global generic market is expected to hit $600 billion. That growth won’t come from cheap aspirin. It’ll come from complex drugs, biosimilars, injectables, and contract services. The future belongs to manufacturers who can adapt-not those who cling to the old model.

The sustainability question: can generics last?

There’s a contradiction at the heart of this industry. Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $400 billion a year. They’re essential. Yet, the system is designed to make them unprofitable.Pay-for-delay deals-where brand companies pay generics to stay off the market-still happen. A 2025 study estimated that banning them would save $45 billion over ten years. But even without those, the system is broken. Manufacturers can’t invest in innovation if they’re barely covering their costs.

Some experts say this is a market failure. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard put it plainly: “Essential medicines are disappearing because no one can profitably make them.”

But others see opportunity. The next wave of patent expirations includes blockbuster drugs like Humira, Eliquis, and Keytruda. When those go generic, the savings will be enormous. The companies that are ready-with complex formulations, reliable supply chains, and smart manufacturing-will be the ones to cash in.

It’s not about making more pills. It’s about making better ones. And making them in a way that keeps the lights on.

Why are generic drug prices falling so fast?

Prices drop because multiple manufacturers enter the market after a brand drug’s patent expires. With dozens making the same pill, they compete on price. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) push for the lowest bid, often selecting the cheapest supplier-even if quality or reliability suffers. This forces margins below 10% on simple generics, making it hard to cover production and compliance costs.

Can generic manufacturers still make a profit today?

Yes, but only if they avoid commodity drugs. Companies focusing on complex generics-like injectables, inhalers, or extended-release tablets-can achieve 40-50% margins. Contract manufacturing is another profitable path. Companies like Teva and Viatris are shifting away from low-margin pills toward these higher-value products and services.

What’s the difference between a simple and complex generic?

A simple generic is a basic tablet or capsule with one active ingredient, easy to replicate-like generic ibuprofen. A complex generic involves advanced delivery systems: patches, inhalers, injectables, or drugs that need precise timing or stability. These require specialized equipment, deeper scientific knowledge, and longer approval times. Fewer companies can make them, so competition is lower and margins are higher.

Why do generic drug shortages keep happening?

Shortages occur when manufacturers can’t make enough profit to justify production. If a drug sells for $3 a bottle and costs $2.80 to make-including compliance, labor, and raw materials-there’s no room for error. A spike in ingredient cost or a factory inspection delay can push a company to stop making it. The system rewards the lowest price, not reliability.

Is contract manufacturing a good option for new companies?

It’s one of the safest entry points. Instead of spending millions on drug development and marketing, a new company can focus on building a compliant, efficient manufacturing facility. Then they lease capacity to established brands or generics companies. This reduces risk, shortens time to revenue, and leverages existing demand without needing a sales team or brand recognition.

What’s next for the generic drug industry?

The future belongs to companies that move beyond pills. Biosimilars, specialty generics, and contract manufacturing are the growth areas. The U.S. market for simple generics will keep shrinking, but global demand for complex, high-quality manufacturing is rising. Manufacturers who invest in technology, regulatory expertise, and supply chain resilience will survive-and even thrive.

Joseph Townsend

Let me tell you something - this whole generic drug system is a goddamn circus. We’re paying for life-saving pills like they’re bulk candy from a gas station. Companies are going bankrupt trying to make metformin while CEOs in white suits sip champagne on yachts. And don’t even get me started on PBMs - those middlemen are the real vampires sucking the blood out of every pill. It’s not capitalism. It’s cannibalism.

Bill Machi

The decline of American manufacturing is not accidental. It is the direct result of decades of neoliberal policy, outsourcing, and the worship of short-term profit over national security. When a nation cannot produce its own essential medicines, it is no longer sovereign. The FDA’s approval process is a bureaucratic maze designed to protect Big Pharma, not patients. This is not a market failure - it is a strategic surrender.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

There is a profound irony here: the very drugs that sustain the lives of millions are rendered economically nonviable by the same system that claims to champion efficiency and cost-reduction. We have created a paradox where compassion is punished by the ledger. The market, left unchecked, does not value life - it values margins. And so, the most vulnerable among us pay the price in silence, while executives calculate their quarterly bonuses. This is not merely a business crisis - it is a moral collapse.

satya pradeep

Bro, I work in pharma logistics in Hyderabad and let me tell you - the real money ain’t in making 10-cent pills. We’re doing contract manufacturing for a Canadian firm that makes inhalers. Margins are solid, no price wars, and we’re getting tech upgrades from them. Simple generics? Dead. Complex stuff? That’s where the game’s at. Also, India’s got the raw materials and the workers - we just need better regulatory clarity. Stop chasing pennies, start building expertise.

Prem Hungry

To everyone feeling hopeless about this: there is still a path forward. It requires vision, not desperation. Focus on quality over quantity. Invest in training your team in advanced formulation science. Partner with research institutions. The world needs reliable manufacturers - not discount drug pushers. You don’t have to compete with the lowest bidder. You can compete on excellence. And excellence always finds a buyer.

Jeremy Hernandez

Big Pharma and the FDA are in cahoots. They let the generics in just enough to look like they’re lowering prices - then they make sure only the big boys can afford the approval process. It’s a monopoly disguised as competition. And don’t tell me about "complex generics" - that’s just a fancy word for "we’re still ripping you off, just slower." The whole system is rigged. Wake up.

Tarryne Rolle

Isn’t it strange how we celebrate the idea of "affordable medicine" while simultaneously punishing anyone who tries to produce it? We want the pills, but we refuse to pay for the infrastructure, the labor, the science - the humanity behind them. We’ve turned healing into a commodity and then act shocked when it breaks. Maybe the problem isn’t the market. Maybe it’s us.

Kyle Swatt

Look I’ve seen factories in Ohio shut down because they couldn’t compete with a Chinese plant selling a 30-day supply of lisinopril for $2. But here’s the thing - that $2 pill? It’s got trace contaminants. The factory skipped stability tests. People are getting sick because we optimized for price, not safety. We’re not saving money - we’re just outsourcing risk. And one day, someone’s kid is gonna die because we chose the cheapest option. That’s not progress. That’s negligence dressed up as economics.

Deb McLachlin

The shift toward contract manufacturing represents a fundamental reorientation of value creation in the pharmaceutical industry. Rather than commoditizing the end product, firms are now monetizing process expertise, regulatory compliance, and scalable infrastructure. This transition aligns with global supply chain trends and may represent a more sustainable economic model, provided that quality assurance remains uncompromised.

saurabh lamba

so like… we’re just supposed to let companies go broke making heart meds? that’s dumb. also why is no one talking about how the u.s. government could just buy the patents and make these drugs themselves? like… we pay for them anyway. why not cut out the middlemen and the price wars? just saying.

Joseph Townsend

^THIS. That’s the real answer. Why does the U.S. let private companies gamble with life-saving drugs? We fund the R&D through NIH, we pay for it through insurance, we bail out hospitals when shortages hit - but we won’t just make the damn pills ourselves? We’re not a country. We’re a shareholder meeting with a flag.