Most people think pharmacies make money because they sell expensive brand-name drugs. But the truth? The real profit engine isn’t the $500 insulin pen or the $1,200 cancer pill. It’s the $5 bottle of generic lisinopril sitting on the shelf next to it. In fact, generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they account for just 25% of total drug spending. And yet, they generate nearly all of a pharmacy’s profit.

Here’s the paradox: brand-name drugs cost more, so you’d assume they bring in more money. But pharmacies make, on average, 42.7% gross margin on generics versus just 3.5% on brand-name drugs. That’s more than 12 times the profit per prescription. A $10 generic drug might earn a pharmacy $4.27 in gross profit. A $500 brand drug? Maybe $17.50. But here’s the catch - pharmacies sell 100 generics for every 10 brand-name prescriptions. So even though brand drugs soak up most of the patient’s out-of-pocket cost, the real money comes from volume and markup on cheap generics.

How the System Actually Works

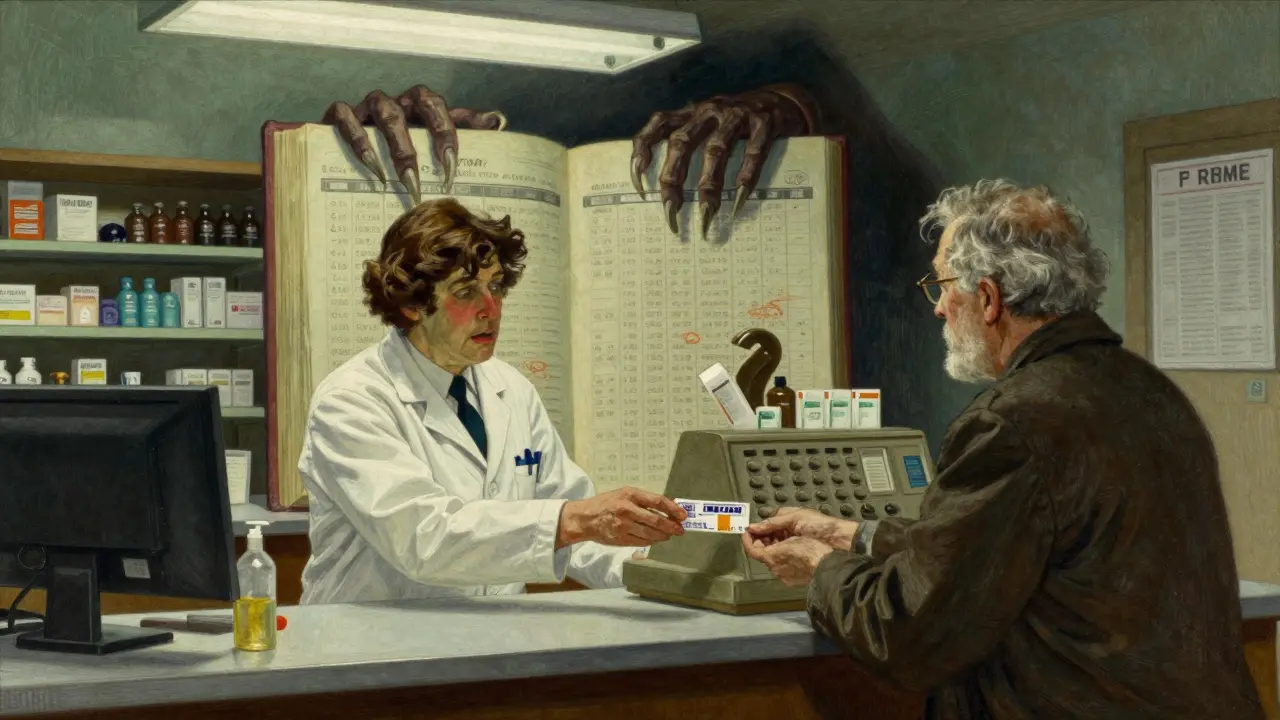

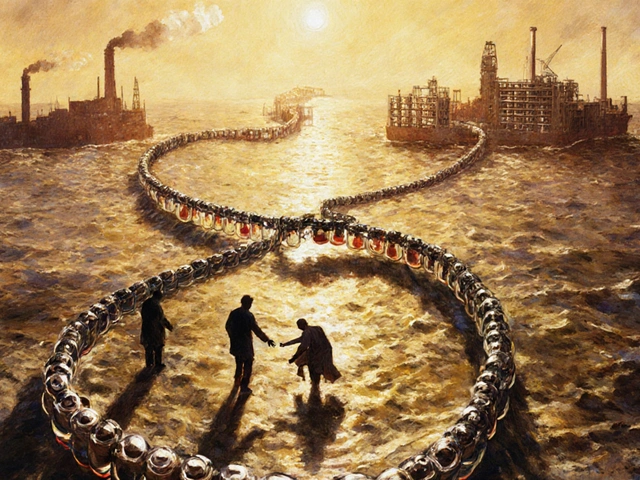

The pharmacy doesn’t buy drugs at the list price. It buys them from wholesalers, who get them from manufacturers. Then the pharmacy gets reimbursed by insurance plans - but not directly. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx act as middlemen. They negotiate prices with manufacturers and set what pharmacies get paid.

Here’s where it gets messy. PBMs often use something called “spread pricing.” They tell the insurance plan they paid $15 for a generic drug. But they only pay the pharmacy $10. The $5 difference? That’s the PBM’s profit. The pharmacy gets paid $10, but it still has to cover rent, staff, utilities, and inventory. That’s why many pharmacies operate at a net profit of just 2% per prescription - after all expenses.

And it’s not just spread pricing. PBMs also use “clawbacks.” If a patient pays a copay of $10 for a generic, but the PBM reimburses the pharmacy only $8, the pharmacy keeps the $2. But if the PBM later finds out the actual cost of the drug was $6, they demand the pharmacy pay back the $2. Sometimes, the pharmacy has to pay out of pocket. That’s not a mistake - it’s a business model.

Why Generics Are the Profit Engine

Generics are cheap to make. Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, other companies can copy it. The FDA approves these copies quickly. When five or six companies make the same generic, prices drop - sometimes by 80% in a year. But pharmacies don’t always pass those savings to customers. Instead, they keep the markup high.

For example, a 30-day supply of generic metformin might cost a pharmacy 8 cents per pill. The patient pays $4. The pharmacy’s gross margin? Around 90%. That’s why pharmacies push generics. It’s not altruism - it’s survival.

But competition among generic manufacturers is slowing. In 2015, the top five generic makers controlled 32% of the market. By 2023, they controlled 45%. Fewer players mean less price pressure. In some cases, when only one company makes a generic, prices spike. There are documented cases where a single-source generic cost more than the original brand drug. That’s not a glitch - it’s market failure.

The Independent Pharmacy Crisis

Independent pharmacies are getting crushed. They make up 40% of U.S. pharmacies but fill only 11% of prescriptions. Why? They can’t negotiate with PBMs the way big chains can. A single independent pharmacy might get reimbursed $7 for a generic that costs $6.50 to buy. After payroll, rent, and insurance, they’re lucky to break even.

Between 2018 and 2023, about 3,000 independent pharmacies shut down. Many owners say they’re working 60-hour weeks just to stay afloat. One owner in Ohio told Pharmacy Times his net profit on generics dropped from 8-10% five years ago to barely 2% today - while his overhead rose 35%.

Big chains like CVS and Walgreens have an advantage. They own their own PBMs. They can shift profits between departments. If the pharmacy loses money, the PBM makes up for it. Or they offer mail-order services, where margins on generics are up to four times higher than in-store.

What’s Changing?

Some new players are trying to fix this. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company sells generics for $20 plus a $3 dispensing fee. No spreads. No clawbacks. Just transparent pricing. Amazon Pharmacy does something similar - $5 for most generics, with clear cost breakdowns.

States are stepping in, too. California, Texas, and Illinois passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose how much they pay pharmacies. The FTC is investigating PBM practices. And the Inflation Reduction Act, starting in 2026, will let Medicare negotiate drug prices - which could reduce pressure on pharmacies by lowering overall drug spending.

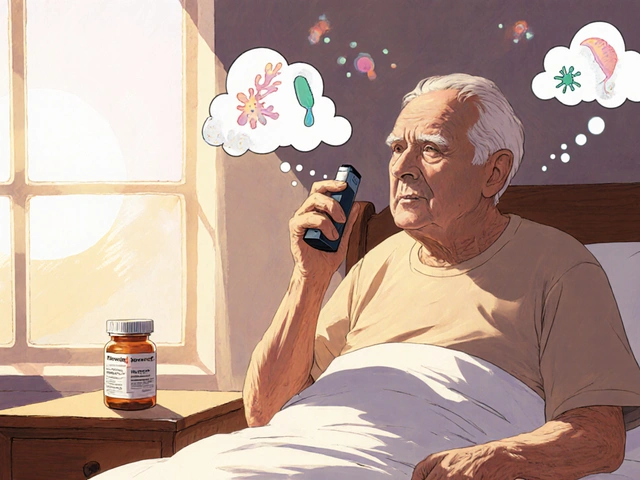

But the biggest shift is happening at the pharmacy counter. Successful independent pharmacies aren’t just dispensing pills anymore. They’re offering medication therapy management (MTM). They check in with patients on blood pressure, diabetes, or cholesterol meds. They bill insurance for those services. That’s where real profit is growing - not in the markup on pills, but in the value they provide.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you’re paying more than you think. That $4 generic copay? A big chunk of it isn’t going to the pharmacy. It’s going to the PBM. The pharmacy just gets the crumbs. That’s why some people are choosing cash pay - sometimes it’s cheaper than using insurance.

If you’re a pharmacy owner, your survival depends on three things: diversifying revenue (MTM, immunizations, compounding), cutting out PBM middlemen where possible, and finding ways to stand out. Chains can compete on scale. Independents have to compete on trust.

And if you’re wondering why your local pharmacy feels more like a warehouse than a health hub - now you know. It’s not about the drugs. It’s about the system. And that system was built to profit from low-cost generics, not to serve patients.

Vu L

Bro, generics are the real villain here. You think pharmacies are getting rich? Nah. They’re just the suckers holding the bag while PBMs laugh all the way to the bank. I’ve seen pharmacists cry over clawbacks. It’s not capitalism-it’s feudalism with a white coat.

James Hilton

So let me get this straight… we’re paying $4 for a pill that costs 8 cents… and the pharmacy gets $2? Meanwhile, my insurance company thinks I’m dumb enough to believe that’s fair? 😂

Mimi Bos

i just wnted to say i had a genric for my blood presser and it cost me 5 dollers at my local phamarcy and they were so nice and asked how i was doin lol

Payton Daily

This whole system is a metaphor for America. The rich get richer by pretending they’re helping you. The generics? They’re the working class-cheap, abundant, and exploited. The PBMs? They’re the landlords. The pharmacies? They’re the tenants who clean up the mess but never get paid. And you? You’re the tenant paying rent to the landlord… while the landlord’s buddy owns the building, the water, and the lights. We’re all just NPCs in a game rigged since day one.

Kelsey Youmans

It is deeply concerning that the structural incentives within the pharmaceutical supply chain have become so misaligned with patient welfare. The erosion of independent pharmacy viability represents not merely an economic shift, but a systemic failure in healthcare accessibility.

Sydney Lee

Let’s be honest: if you’re not using cash to pay for generics, you’re subsidizing the PBM oligopoly. The fact that people still trust insurance for this is the real tragedy. I’ve paid $3.50 cash for metformin at my local pharmacy-no insurance, no middlemen. The pharmacy made more. I paid less. Everyone wins. Except the PBMs. And that’s exactly how it should be.

oluwarotimi w alaka

usa pharma is a joke. why we let them do this? in nigeria we have no generics but we dont pay 500 doller for insulin. they make it cheap there. usa got rich by stealing medicine from poor countries then charge you 10x. this is not free market this is war on poor people

Debra Cagwin

It’s so important to recognize that independent pharmacies are more than businesses-they’re community lifelines. The fact that so many are closing breaks my heart. But there’s hope: MTM services, immunizations, and patient relationships are where the future lies. Keep showing up, pharmacists-you’re doing vital work.

Hakim Bachiri

MARK CUBAN?!!??!!? He’s not a hero-he’s a capitalist opportunist. He’s not fixing the system-he’s just carving out his own slice of the same rotten pie. And Amazon? Don’t even get me started. They’ll bury the last independent pharmacy under data and delivery fees. This isn’t innovation. It’s consolidation with a smiley face.

Celia McTighe

❤️ I love that some pharmacies are shifting to MTM! My grandma’s pharmacist checks in on her every month now-she’s got her diabetes under control because someone actually cares. It’s not about the pills. It’s about the person. 🌱

Ryan Touhill

It’s fascinating how the economic architecture of pharmaceutical distribution has evolved into a parasitic structure where value extraction is prioritized over value creation. The pharmacy, once a sanctuary of care, is now a transactional node in a machine designed to siphon surplus from the vulnerable. The irony? The very drugs meant to heal are now instruments of systemic exploitation. And yet, we call this progress.