Why does a common diabetes drug cost $200 in the U.S. but just $52 in Japan? Or why does a heart medication cost ten times more in the U.S. than in Germany? These aren’t hypothetical questions-they’re everyday realities for millions of people. The truth is, pharmaceutical prices vary wildly across countries, and the reasons aren’t as simple as ‘the U.S. is expensive.’ It’s a mix of policy, market power, and how we measure cost.

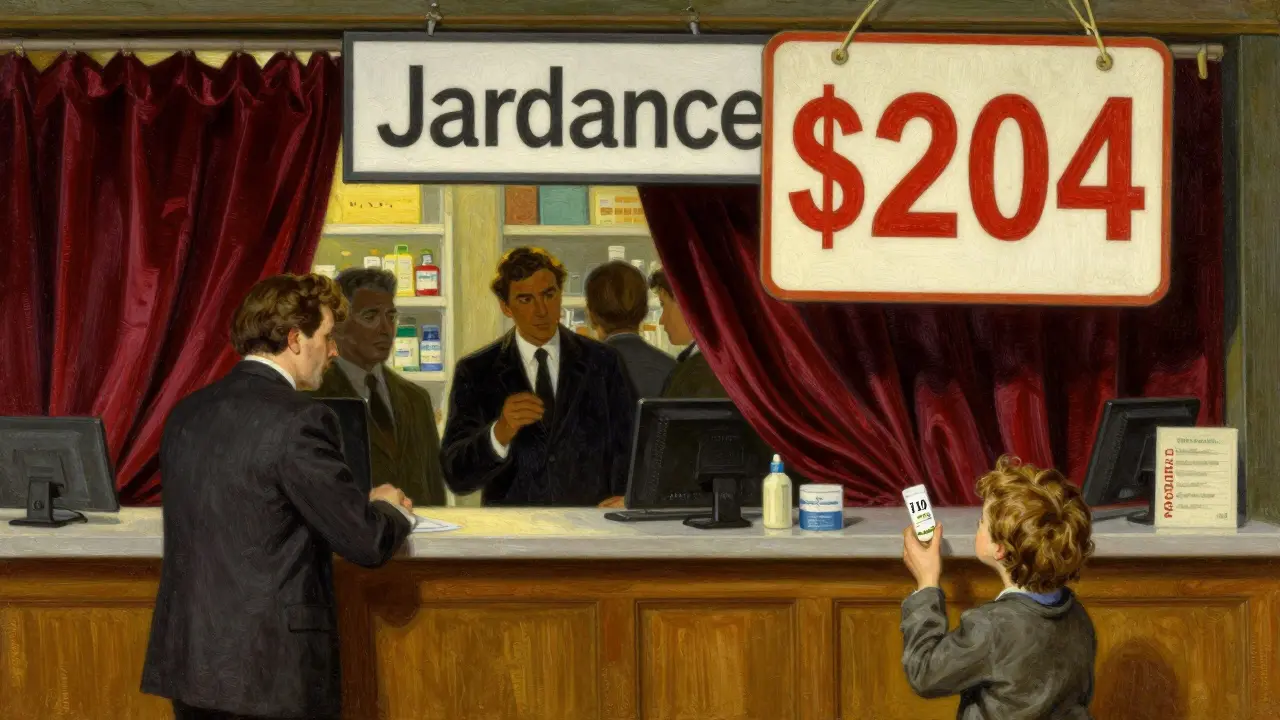

U.S. Drug Prices: Higher List Prices, Lower Net Costs

If you look at the sticker price-the list price-of brand-name drugs in the U.S., it’s shocking. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. list prices for brand-name drugs are more than four times higher than in other wealthy countries. For example, Medicare’s negotiated price for Jardiance, a diabetes drug, is $204. In Japan, it’s $52. In Australia, it’s $58. That’s a 3-to-4x difference.

But here’s what most people don’t see: those list prices rarely matter to most Americans. Only about 7% of prescriptions in the U.S. are for brand-name drugs. The rest-90%-are generics. And here’s the twist: U.S. generic drug prices are among the lowest in the world. On average, they’re 33% cheaper than in other countries. So while you might hear about $1,000 insulin pills in the news, most Americans pay $10 or less for the generic version.

The U.S. system isn’t broken because it’s expensive-it’s broken because it’s confusing. The same drug can cost $100 at the pharmacy counter but only $5 after insurance and rebates. The list price is just the starting point. Pharmacies, insurers, and government programs negotiate deep discounts behind the scenes. That’s why the University of Chicago found that when you look at net prices (what’s actually paid after discounts), the U.S. isn’t the most expensive country anymore. In fact, for public-sector prescriptions, U.S. net prices are 18% lower than in Canada, Germany, France, and the UK.

How Other Countries Control Prices

Most developed countries don’t let drugmakers set prices freely. They use tools like reference pricing, price caps, and direct government negotiation.

In Europe, countries like Germany and the UK use external reference pricing. That means they look at what other countries pay for the same drug and set their own price below the average. France and Japan often end up with the lowest prices because they’re aggressive about negotiating and don’t hesitate to delay approval if the price is too high.

Japan’s system is especially effective. For nearly every major drug-Jardiance, Entresto, Enbrel, Imbruvica-Japan consistently has the lowest price among OECD countries. That’s not luck. It’s policy. The Japanese government has a national drug pricing committee that meets regularly to review and cut prices. They don’t wait for public outrage-they act before costs spiral.

Canada uses a similar approach. Its Patented Medicine Prices Review Board sets price caps based on international benchmarks. Canada’s prices are higher than Japan’s, but still far below U.S. list prices. The UK’s NHS negotiates directly with drugmakers through the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which evaluates whether a drug is worth the cost based on health outcomes. If it’s not cost-effective, it doesn’t get funded.

Medicare’s New Power to Negotiate

The U.S. has been the outlier-until now. For decades, Medicare was legally barred from negotiating drug prices. That changed with the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Starting in 2025, Medicare will begin negotiating prices for 10 high-cost drugs, including Eliquis, Ozempic, and Xarelto.

The first 10 negotiated prices were announced in 2023. The results? Medicare’s prices are still 2.8 times higher than the average in 11 other countries. For Stelara, a rheumatoid arthritis drug, Medicare’s price is $4,490. In the UK, it’s $2,822. In Japan, it’s $1,850. Even after negotiation, the U.S. is paying more than most.

But this is just the beginning. Medicare must release its next list of drugs for negotiation by February 1, 2025. That means more price cuts are coming. And if these negotiations work, they could set a new standard. Right now, private insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are the ones negotiating. But they’re not required to pass savings on to patients. Medicare, as a public program, has more leverage-and more accountability.

Why Some Countries Pay More Than Others

It’s not just about policy-it’s about wealth, population size, and healthcare structure.

A 2024 study in JAMA Health Forum analyzed 549 essential medicines across 72 countries. When adjusted for purchasing power, prices in Argentina were nearly six times higher than in Germany. In Lebanon, they were less than one-fifth. Why? Because in low-income countries, governments can’t afford to pay high prices. So they import generics, use parallel imports, or simply don’t stock certain drugs at all.

Regionally, the Americas had the highest median drug prices, followed by Europe. The Western Pacific (including Japan, Australia, and South Korea) had the lowest. That’s not random. It reflects how tightly those countries control pricing. Australia, for example, has one of the most efficient systems. It uses the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) to set prices and cover most medications at low cost to patients.

China’s approach is also worth noting. Through its national drug negotiation program, it slashed prices for cancer drugs by 50-70% in just a few years. That’s not magic-it’s centralized bargaining power. When a single entity negotiates for 1.4 billion people, drugmakers have little choice but to lower prices.

The Innovation Argument: Are High U.S. Prices Justified?

Drugmakers argue that high U.S. prices fund innovation. They say if prices were lower everywhere, fewer new drugs would be developed. That’s partly true. The U.S. does lead in biotech innovation. Most new cancer drugs, rare disease treatments, and mRNA vaccines are developed by American companies.

But here’s the counterpoint: the U.S. doesn’t pay more because it’s funding global R&D-it pays more because it’s the only major market that doesn’t cap prices. A 2024 analysis from the University of Chicago found that U.S. pricing is ‘efficient’ not because it supports innovation, but because it separates the market: high prices for brands, low prices for generics. That allows drugmakers to profit on new drugs while keeping routine medications affordable.

That model works for big pharma. It doesn’t always work for patients. Someone with a rare disease who needs a $500,000 drug every year doesn’t benefit from low generic prices. And when Medicare starts negotiating, those same drugmakers may cut R&D budgets in other areas, or delay launches in countries where prices are low.

What This Means for Patients

If you’re in the U.S., your out-of-pocket cost depends on your insurance, whether the drug is generic or brand, and where you live. Some states have laws capping insulin prices at $35. Others have no protections at all.

If you’re in Canada or the UK, you pay a fixed co-pay-usually under $30-for most prescriptions, no matter the drug’s list price. In Germany, you pay up to 10% of the drug’s cost, capped at €10 per month. In Japan, you pay 10-30% depending on age and income, with monthly caps.

The biggest takeaway? The system you’re in matters more than the drug you need. A patient in France can get the same medication as a patient in the U.S. for a fraction of the cost. But the U.S. patient might pay nothing if it’s a generic. The difference isn’t about fairness-it’s about structure.

The Future of Drug Pricing

Medicare’s negotiations are just the start. More countries are adopting reference pricing. The EU is pushing for joint procurement-buying drugs together across borders to increase bargaining power. India and Brazil are expanding their generic manufacturing capacity, which will keep pushing global prices down.

But the U.S. still has the most complex system. It’s a mix of public and private players, with no single entity controlling prices. That means confusion, inconsistency, and sometimes, exploitation. The Inflation Reduction Act is a step toward balance. But real change will come when patients demand transparency-when they ask not just ‘how much does this cost?’ but ‘why does it cost this much?’

For now, the global picture is clear: countries that negotiate, cap, or compare prices pay less. Countries that don’t, pay more. And the U.S. is finally joining the group that’s trying to fix it.

Why are drug prices so much higher in the U.S. than in other countries?

U.S. drug prices are higher because the government doesn’t negotiate prices for most drugs, and drugmakers can set list prices without limits. Unlike countries that use reference pricing or price caps, the U.S. relies on private insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to negotiate discounts behind the scenes. This system keeps list prices high, even though most Americans pay much less thanks to generics and rebates.

Do Americans pay more for generic drugs?

No. In fact, Americans pay less for generics than people in most other countries. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S., and their prices are about 33% lower than the international average. This is because of strong competition among U.S. generic manufacturers and bulk purchasing by large pharmacy chains and insurers.

Which country has the lowest drug prices?

Japan consistently has the lowest prices for brand-name drugs among wealthy nations. Countries like France, Australia, and Germany also have very low prices due to strict government negotiation and reference pricing systems. Japan’s national pricing committee reviews and lowers drug prices regularly, often cutting them by 20-40% after a drug’s patent expires.

How does Medicare’s new drug negotiation work?

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, Medicare can now negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs each year starting in 2025. The first 10 drugs were selected based on spending and lack of generic competition. Medicare sets a maximum price, and drugmakers must agree to it or lose access to the Medicare market. This is the first time the U.S. government has had direct negotiating power for prescription drugs.

Are high U.S. drug prices funding global innovation?

It’s a common argument, but evidence is mixed. While the U.S. does lead in biotech innovation, most new drugs are developed by companies that sell globally. Countries with lower prices still pay for innovation through taxes and public funding. Studies show that even if U.S. prices dropped to match other countries, innovation wouldn’t stop-it would just shift funding sources. The real issue is whether the current system is the most efficient way to fund it.

Can I buy cheaper drugs from other countries?

Legally, importing prescription drugs from other countries is not allowed in the U.S., except under very limited circumstances. However, some Americans use international pharmacies or travel abroad to fill prescriptions. Many countries sell the same drugs under the same brand names at much lower prices. While it’s risky without medical oversight, some patients do it to save money-especially for chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

Nicole K.

Why do we let these drug companies get away with this? It's pure greed. People are choosing between medicine and groceries, and nobody's doing anything real about it.

Sharleen Luciano

Let’s be honest - the U.S. pharmaceutical model isn’t broken, it’s *optimized*. The list price is a theatrical prop for investors, while the net price is where the real ballet of rebates, PBMs, and insurer carve-outs takes place. The average American doesn’t pay sticker - they pay the shadow price, invisible to the naked eye. But the system? It’s a Rube Goldberg machine of middlemen, each taking a cut. And yes, generics are dirt cheap - because they’re commoditized. The real tragedy is that innovation is held hostage by the very structure meant to fund it.

Teresa Rodriguez leon

I had to choose between my insulin and my rent last winter. I skipped doses. I’m still alive. But I shouldn’t have had to make that choice. Not in America. Not in 2025.

Manan Pandya

Japan’s pricing model is a textbook example of effective public policy. The government doesn’t just negotiate - it enforces. By setting benchmarks based on international prices and reviewing them regularly, they prevent monopolistic pricing without stifling innovation. The U.S. could learn from this, but political inertia and lobbying power make reform difficult. Still, Medicare’s new authority is a promising step - if implemented transparently and without loopholes.

Aliza Efraimov

My mom’s on Eliquis. She pays $12 a month because of a patient assistance program. But what if she didn’t have a son who knew how to navigate the system? What if she was 78, alone, and didn’t speak English? That’s the real crisis - not the sticker price, but the maze. The system isn’t broken because it’s expensive - it’s broken because it’s *unfair*. And now Medicare’s finally stepping in. Thank God. I cried when I heard the news.

Tamar Dunlop

As a Canadian, I must emphasize that our system is not perfect - we wait for drugs, we have formulary restrictions, and sometimes access is delayed. But we do not face financial ruin because of a prescription. The PBS ensures that even the most expensive medications are available at a nominal cost. When I visited the U.S. last year and saw the price of a single inhaler - $400 - I was horrified. We are not ‘socialist’; we are simply civilized.

Emma Duquemin

Y’all are acting like this is new news. Let me tell you - I’ve been calling out Big Pharma since 2018. The U.S. is the only country where you get billed for the *marketing budget* of a drug. The list price? That’s the price of a billboard. The real price? The one after rebates? That’s what matters. But guess what? Patients don’t see that. They see the $700 insulin at the counter. And that’s the horror story. Medicare negotiating? It’s about damn time. Now let’s make PBMs disclose their cuts - that’s the next battle.

Duncan Careless

yeah i read this and thought… well at least we dont have the us system. but then i remembered our wait times for new cancer meds. its a tradeoff. not perfect, but better than being bankrupted by a pill.

Samar Khan

So let me get this straight… Americans pay less for generics because they’re cheap… but the brand-name drugs are 4x more expensive because ‘the system works’? 😂 That’s not a system, that’s a pyramid scheme with doctors and insurers as the middlemen. And don’t even get me started on PBMs - they’re the real villains. 💸 #PharmaScam

Russell Thomas

Oh wow, so the U.S. isn’t actually the most expensive country… according to the *net* price? 😂 That’s like saying your car isn’t expensive because you got a 90% discount - but the sticker’s still $150,000. Meanwhile, I’m paying $500 for my insulin because my insurance won’t cover the generic *because the manufacturer blocked it*. Thanks, capitalism.

Joe Kwon

From a systems perspective, this is a classic principal-agent problem: patients are the principals, but insurers and PBMs are the agents negotiating on their behalf - and they’re not incentivized to pass savings to consumers. Medicare stepping in as a direct negotiator aligns incentives. The real innovation here isn’t the drug - it’s the institutional design. If we can scale this model to private payers, we could finally decouple drug pricing from market power and tie it to value. The next frontier? Transparent rebate reporting and anti-gag clauses. This is just Phase 1.