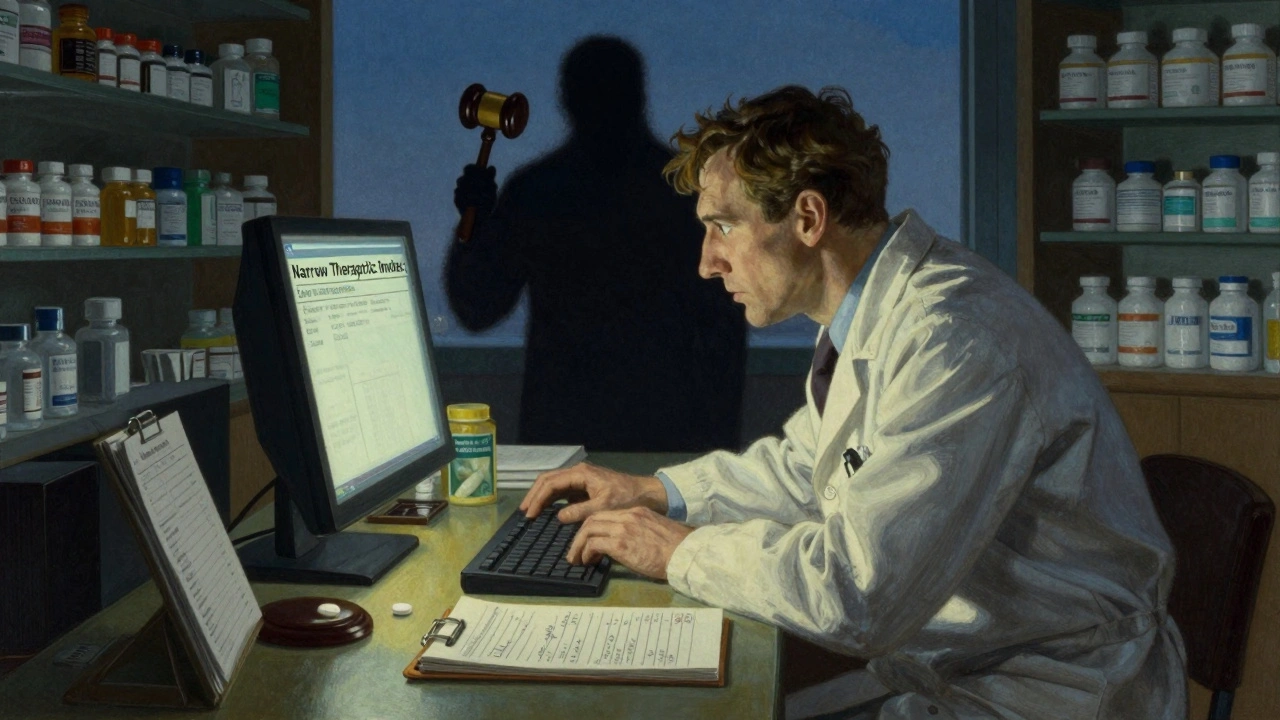

When a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic version, they’re not just saving money-they’re stepping into a legal gray zone. In 2025, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, saving patients and the system billions each year. But behind that efficiency lies a growing risk: professional liability. If a patient has a bad reaction after a generic substitution, who’s responsible? The pharmacist? The manufacturer? The doctor? The answer isn’t simple-and it varies by state.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t Just a Cost-Saving Move

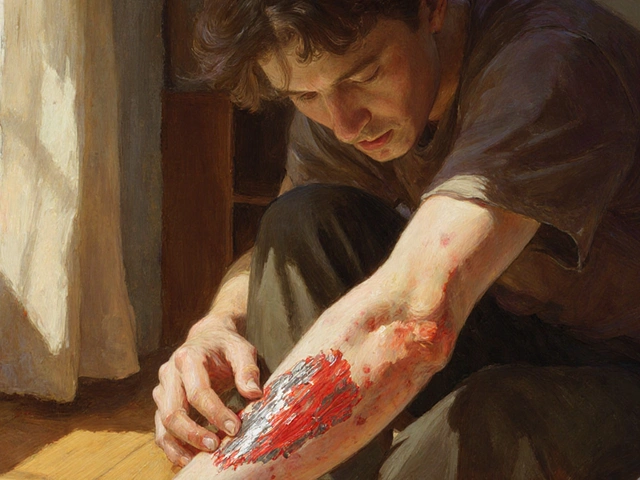

Generic drugs aren’t copies. They’re required to have the same active ingredient, strength, and route of administration as the brand-name version. But they can differ in fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes. For most medications-like statins or blood pressure pills-these differences don’t matter. The body absorbs them the same way. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, even tiny variations can be dangerous. Think of warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications like phenytoin. These drugs need to stay within a very tight range in the bloodstream. Too little, and the condition returns. Too much, and you risk toxicity. A 2017 study in Epilepsy & Behavior found that 18.3% of patients experienced therapeutic failure after switching from brand to generic antiepileptic drugs. Some patients had seizures. Others developed dizziness, confusion, or even permanent neurological damage. And here’s the kicker: federal law says generic manufacturers can’t change their labels-even if they discover a new safety issue. That’s because of the 2011 Supreme Court case PLIVA v. Mensing. The ruling said generic drug makers can’t be sued under state law for failing to update warnings. Why? Because they’re legally required to use the same label as the brand-name drug. So if a patient is harmed, they can’t sue the maker of the generic they took. And they usually can’t sue the brand-name maker either, because they didn’t make the product.State Laws Are a Patchwork-And So Is Liability

Each state has its own rules about when and how pharmacists can substitute generics. There’s no national standard. In 27 states, pharmacists are required to substitute generics unless the doctor says “do not substitute.” In 23 others, substitution is allowed but not mandatory. And in 23 states, pharmacists get no legal protection if something goes wrong. In states like California, Texas, and Florida, laws explicitly say pharmacists aren’t liable for substitution as long as they follow the rules. But in Connecticut and Massachusetts, there’s no such shield. Pharmacists there have seen 27% more malpractice claims related to substitution, according to a 2019 National Community Pharmacists Association study. Even worse, only 18 states require pharmacists to tell patients directly that a substitution was made. That means 32 states let pharmacists swap drugs without the patient ever knowing. A 2021 Patient Advocacy Foundation survey found that 41% of patients didn’t realize their prescription had been switched until they started feeling sick.Who’s at Risk? The Pharmacist

Pharmacists are on the front lines. They’re the ones handing out the pills. They’re the ones who see the patient’s reaction. And if something goes wrong, they’re often the first target. A 2022 survey of 452 pharmacists by Pharmacy Times found that 74% had refused to substitute a generic for a narrow therapeutic index drug-even when state law allowed it-because they were afraid of being sued. One pharmacist in Ohio told a reporter: “I won’t swap levothyroxine. Not because I think it’s unsafe. Because I can’t afford to lose my license over a $5 difference.” The liability risk isn’t theoretical. In 2019, a patient in Pennsylvania suffered permanent brain damage after switching to a generic antiepileptic. The court dismissed the case because federal law blocked liability against the generic manufacturer. The pharmacist wasn’t named in the lawsuit, but the family’s attorney said they would have sued if state law allowed it. The pharmacist now carries supplemental malpractice insurance just for substitution risks.

How to Reduce Risk: A 7-Step Protocol

You can’t eliminate all risk-but you can dramatically reduce it. Here’s what works, based on the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists’ 2022 guidelines:- Know your state’s laws. Every year, check the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s compendium. Laws change. In 2023, 11 states introduced new bills to address substitution liability. Don’t rely on memory.

- Use EHR alerts. Set up electronic health record flags for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices. If a prescription for levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin comes in, the system should pop up a warning: “Check substitution rules.”

- Get written consent. If your state allows it, have patients sign a simple form before substituting. Even if not required, it shows you took responsibility seriously. Use a standardized template-don’t make it up.

- Communicate with prescribers. If you’re unsure about substitution, call the doctor. Many physicians don’t realize how dangerous switching can be for certain drugs. A quick conversation can prevent a disaster.

- Log every substitution. Record the brand name, generic name, lot number, and date. If a problem arises later, you need to trace exactly what was dispensed. Batch numbers matter.

- Do an annual risk assessment. Use the 27-point checklist from the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. It covers everything from patient counseling to insurance coverage.

- Get extra insurance. Standard malpractice policies often exclude substitution-related claims. Buy a rider that specifically covers generic substitution liability. It costs $300-$800 a year. Worth it.

The Bigger Picture: Who’s Responsible?

The system is broken. Patients get cheaper drugs, but they’re also getting less protection. Manufacturers avoid liability, doctors rarely know what’s being swapped, and pharmacists are left holding the bag. Some experts, like Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard, argue for a “consensus labeling” system. Imagine one standardized label for all versions of a drug-brand or generic-that gets updated whenever new safety data emerges. That way, everyone uses the same warning, and no one can claim ignorance. Other solutions are being tested. In 2023, 5 states started a pilot program under the Interstate Pharmacy Compact to share safety data and create uniform substitution rules. The FDA’s 2023 pilot for label changes has approved 68% of requests-but generic manufacturers only initiated 12% of them. That tells you who’s afraid to speak up. Meanwhile, the cost of doing nothing is rising. The Congressional Budget Office estimates unaddressed adverse events from substitution will cost the system $4.2 billion annually by 2028. That’s not just money-it’s lives.

What Patients Need to Know

Patients aren’t always informed. They assume the pharmacist is just following orders. But they have rights. In 32 states, patients can refuse a generic substitution. In 18 states, pharmacists must tell them before swapping. But most patients don’t know that. If you’re on a drug like levothyroxine or warfarin, ask: “Is this the same brand as before?” If the answer is no, ask why. And if you feel worse after a switch, tell your doctor immediately. A 2023 GoodRx survey showed 82% of patients were happy with generic substitutions for common drugs like metformin and lisinopril. But for high-risk meds? The satisfaction rate drops to 51%. That gap matters.The Future Is Uncertain-but Action Is Possible

Generic substitution will keep growing. Biosimilars-generic versions of biologic drugs-are now entering the market. Forty-five states have passed laws allowing them, but liability rules are even murkier. The path forward isn’t about stopping substitution. It’s about making it safer. Clearer rules. Better communication. Shared responsibility. And accountability where it belongs. Pharmacists can’t fix the system alone. But they can protect themselves-and their patients-by being informed, documented, and proactive. The law won’t change overnight. But your practice can.Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes, but only under certain conditions. Federal law shields generic manufacturers from liability for labeling issues, but pharmacists can still be held responsible under state law if they fail to follow substitution rules-like not getting required patient consent, substituting without checking for narrow therapeutic index drugs, or failing to document the switch. Liability depends on state law, documentation, and whether the pharmacist acted negligently.

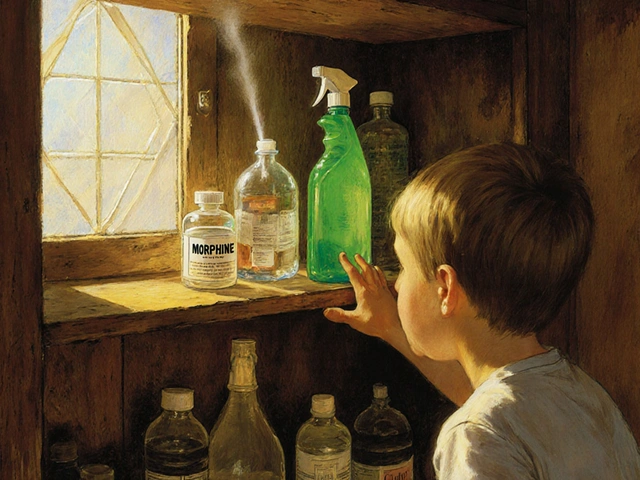

Which drugs are most dangerous to substitute?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index are the highest risk. These include warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), phenytoin and other antiepileptics, lithium, and cyclosporine. Small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm-seizures, strokes, organ failure, or death. The American Epilepsy Society and FDA both warn against routine substitution for these drugs.

Do I have to tell my patient if I substitute a generic?

It depends on your state. Eighteen states require direct patient notification beyond what’s on the label. In 32 states, patients can refuse substitution if they’re told-so disclosure is legally required there too. Even if your state doesn’t require it, best practice is to always inform patients, especially for high-risk medications. Documentation protects you.

Can I refuse to substitute a generic even if the law allows it?

Yes. Pharmacists have the right-and sometimes the ethical duty-to refuse substitution if they believe it could harm the patient. Many pharmacists refuse to substitute antiepileptics, thyroid meds, or warfarin even in states where it’s permitted. This is considered professional judgment, not negligence, as long as you document your reasoning and communicate with the prescriber.

What’s the best way to protect myself from liability?

Use a 7-step protocol: 1) Know your state’s laws, 2) Use EHR alerts for high-risk drugs, 3) Get written patient consent, 4) Talk to the prescriber when unsure, 5) Log every substitution with batch numbers, 6) Do an annual risk assessment, and 7) Buy supplemental malpractice insurance for substitution risks. These steps reduce your exposure and show you acted responsibly.

Are generic drugs always safe?

For most medications-like antibiotics, statins, or blood pressure pills-yes. Generic drugs are safe and effective for the vast majority of patients. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, even small differences in formulation can lead to therapeutic failure or toxicity. The issue isn’t safety in general-it’s precision. When the margin for error is tiny, generics aren’t always interchangeable.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means the generic drug is absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent as the brand-name drug-usually within 80-125% of the original. But therapeutic equivalence means the drug produces the same clinical effect and safety profile. A drug can be bioequivalent but not therapeutically equivalent, especially in sensitive populations or with narrow therapeutic index drugs. The FDA’s Orange Book lists therapeutic equivalence codes, but many pharmacists don’t check them.

Kyle Flores

I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years and I still get nervous every time I swap levothyroxine. Not because I think generics are bad-most are fine-but because one patient’s seizure changed everything for me. I started documenting everything after that. Signed consent forms, batch numbers, even notes like ‘patient said they felt ‘off’ last time.’ It’s a pain, but it’s worth it. I sleep better now.

Also, tell your patients. Even if your state doesn’t require it. They deserve to know.

And yeah, I buy the extra insurance. $500 a year beats losing my license.

Ryan Sullivan

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a liability issue-it’s a systemic failure of regulatory capture. The FDA’s therapeutic equivalence framework is a charade. Bioequivalence ≠ therapeutic equivalence, yet we treat them as synonyms. Generic manufacturers exploit this loophole, and pharmacists are the sacrificial lambs. The fact that we’re expected to act as de facto clinical pharmacologists without training, authority, or legal backing is obscene.

And don’t get me started on the 32 states that don’t require disclosure. That’s not negligence-it’s institutionalized malpractice.

Wesley Phillips

Bro. I just had a patient ask me why her ‘new’ seizure med made her feel like she was underwater. Turns out she’d been on the brand for 8 years. I swapped it because the insurance wouldn’t cover it. She didn’t know. I didn’t know the label didn’t change. Now I’m terrified.

Also, I just bought a t-shirt that says ‘I substituted and all I got was this lousy malpractice suit.’

TL;DR: This is a mess. We need a national standard. And someone needs to tell the FDA to stop pretending generics are all the same.

Olivia Hand

Did you know that the FDA’s Orange Book lists therapeutic equivalence codes-but most community pharmacies don’t even check them? I’ve asked 3 different techs in my store if they know what ‘AB1’ means. Two said ‘is that a drug?’ One said ‘is it gluten-free?’

It’s not just about laws or insurance. It’s about training. We’re expected to make high-stakes clinical decisions with zero standardized education on bioequivalence. How is that acceptable?

Also, why are we still using paper logs? My EHR could auto-flag narrows and auto-populate consent forms. But nope. We’re still printing forms in 2025.

Desmond Khoo

Y’all are overthinking this 😅

Most people are fine with generics. Like, 82% of folks on metformin don’t even notice the switch. But yeah, for warfarin or phenytoin? Don’t mess with it. Just don’t.

I started putting a little sticky note on the bag: ‘This is a generic. If you feel weird, call us.’

It’s simple. It’s cheap. It’s human.

Also, get the extra insurance. It’s like buying a helmet. You don’t need it… until you do. 💪🩺

Louis Llaine

So let me get this straight. We’ve got a system where drug companies can’t be sued, doctors don’t care, patients don’t know, and pharmacists are left holding the bag because… capitalism?

Wow. Just wow.

At this point, I just tell patients ‘your pill is different’ and hand them a free lollipop. That’s the extent of my risk mitigation. The rest? Pure luck.

Jane Quitain

I just started working in a pharmacy and I read this and I cried a little 😭

It’s so scary to think one little mistake could ruin someone’s life… and your career. But I want to do this right. I’m going to start with the 7-step thing. I’m printing it out. I’m laminating it. I’m putting it by the register.

Also, I’m going to ask my boss if we can do patient education sheets. Like, a little card that says ‘This is a generic. Here’s what to watch for.’

We can do better. We have to.

Kyle Oksten

The real question isn’t who’s liable-it’s who should be. The system was designed to shift risk downward: manufacturers → regulators → pharmacists → patients. That’s not justice. That’s structural cowardice.

Until we hold the manufacturers accountable for labeling, or force a unified national standard for therapeutic equivalence, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Pharmacists aren’t the problem. We’re the symptom.

Sam Mathew Cheriyan

Bro… what if this is all a Big Pharma scam? I heard the FDA gets paid by the drug companies to approve generics. That’s why they say they’re ‘equivalent’-they’re not. The real drugs are made in India and China with weird fillers that cause seizures. They want you to think it’s safe so you don’t sue them. The pharmacist? Just the patsy.

Also, my cousin’s dog got sick after eating generic flea meds. Coincidence? I think not.

Ernie Blevins

Stop pretending this is complicated. It’s not. Pharmacists are getting sued because they’re bad at their job. If you don’t know the difference between bioequivalent and therapeutic, you shouldn’t be handing out pills.

Also, patients don’t care about your ‘protocol.’ They just want their meds to work. Stop making excuses. Get better or get out.