What Is Autoimmune Uveitis?

Autoimmune uveitis is when your immune system mistakenly attacks the uvea-the middle layer of your eye that includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. This causes inflammation, swelling, and damage that can lead to blurry vision, eye pain, light sensitivity, and even permanent vision loss if not treated. Unlike infections that trigger uveitis, this form is driven by your own immune system going rogue. It’s rare-fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. have it-but it’s serious. It doesn’t just affect your eyes; it often links to bigger autoimmune diseases like ankylosing spondylitis, lupus, Crohn’s, or rheumatoid arthritis.

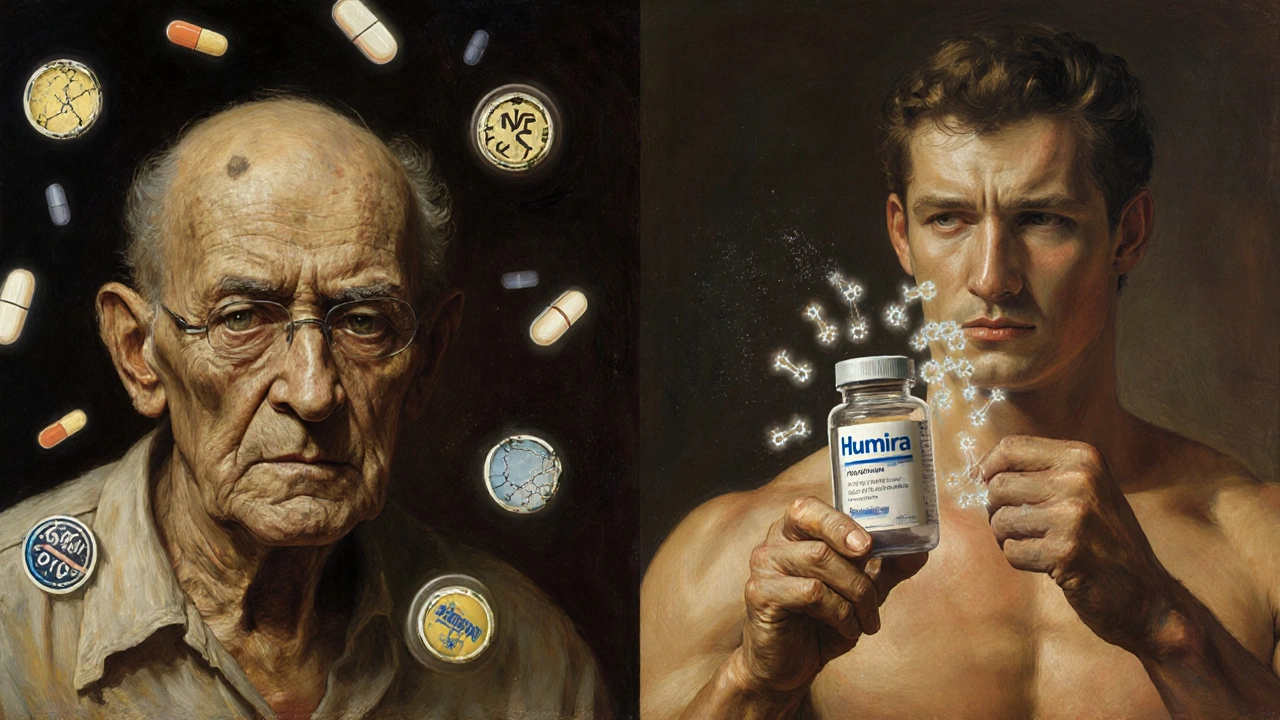

Why Steroids Are Used-And Why They’re Not the Full Answer

Corticosteroids, whether as eye drops, injections, or pills, are the first line of defense. They work fast to calm down inflammation. For someone with sudden, severe uveitis, steroids can mean the difference between keeping their vision and losing it. But here’s the catch: long-term steroid use creates new problems. Cataracts form. Eye pressure rises, leading to glaucoma. Weight gain, bone thinning, high blood sugar, and mood swings become daily struggles. The NHS and Cleveland Clinic both warn that steroids are a bridge, not a destination. If you need them for more than a few months, you’re at risk of damage that’s harder to fix than the original inflammation.

What Is Steroid-Sparing Therapy?

Steroid-sparing therapy means using other drugs to control inflammation so you can reduce or stop steroids altogether. These aren’t experimental-they’re backed by clinical guidelines and real-world use. The goal? Keep your eyes safe without wrecking your body. Common options include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologics like adalimumab (Humira). These drugs don’t just suppress the immune system broadly; they target specific parts of the inflammation pathway. Humira, for example, blocks TNF-alpha, a protein that fuels eye inflammation. It’s the first FDA-approved biologic specifically for non-infectious uveitis, making it a game-changer since its approval in 2016.

How Doctors Decide Which Treatment to Use

There’s no one-size-fits-all. Your treatment depends on three things: where the inflammation is (front, middle, or back of the eye), how bad it is, and whether you have another autoimmune disease. A patient with uveitis tied to Crohn’s might get Humira because it works for both. Someone with mild anterior uveitis might start with methotrexate and eye drops. If you’re a child, doctors might lean toward infliximab-Dr. Nisha Acharya’s research at UT Southwestern showed strong results in pediatric cases, with kids needing far fewer steroids after starting treatment. The key is collaboration. Rheumatologists and ophthalmologists need to talk. A single doctor can’t manage this alone.

How Diagnosis Happens Before Treatment Starts

Before you even get a drug, you need to be sure it’s autoimmune. Infectious uveitis-caused by viruses, bacteria, or parasites-needs antibiotics or antivirals, not immunosuppressants. Mistake the cause, and you make things worse. Diagnosis starts with a slit-lamp exam, then moves to OCT scans to check for swelling in the retina, and fluorescein angiography to see blood flow in the eye. Blood tests look for markers like HLA-B27 (linked to ankylosing spondylitis) or ACE levels (suggestive of sarcoidosis). You might also get an MRI or chest X-ray if sarcoidosis is suspected. Skipping these steps risks giving you the wrong treatment-and that’s dangerous.

The Real-World Impact: Quality of Life After Starting Steroid-Sparing Therapy

Patients who switch from long-term steroids to steroid-sparing drugs often report feeling like themselves again. No more moon face. No more insomnia from prednisone. No more fear of broken bones. But it’s not perfect. Immunosuppressants lower your defenses. You’re more prone to infections-cold sores, urinary tract infections, even pneumonia. Regular blood tests are needed to monitor liver and kidney function. Some people feel nauseous or get headaches. The NHS recommends follow-up visits every few weeks at first, then every few months, to check for side effects and make sure the inflammation stays under control. The trade-off? A better long-term future for your eyes and your body.

What’s Coming Next in Treatment

The field is moving fast. Seven new drugs targeting different parts of the immune system are in clinical trials. Some block interleukins like IL-6 or IL-17, others tweak the JAK-STAT pathway. These could help people who don’t respond to TNF inhibitors. Researchers are also exploring genetic markers and protein signatures that could predict which drug will work best for you-personalized medicine for uveitis. In 2023, specialized uveitis clinics in the U.S. jumped from 15 to over 50. That means more access to experts who know how to balance these complex treatments. The future isn’t just about stopping steroids-it’s about matching the right drug to the right person at the right time.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with autoimmune uveitis, ask your doctor these questions: Is my uveitis linked to another condition? Have we ruled out infection? What’s my plan for reducing steroids? What side effects should I watch for? Don’t wait for symptoms to worsen. Early treatment prevents permanent damage. Keep all your appointments-even if you feel fine. Uveitis can flare without pain. Use reminders for blood tests and eye scans. Join a patient support group. You’re not alone. And if your current treatment isn’t working, speak up. There are options beyond the first drug they give you.

Why This Matters Beyond the Eyes

Autoimmune uveitis doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s a signal that your immune system is out of balance. Treating it isn’t just about saving vision-it’s about managing a whole-body condition. The same drugs that help your eyes might also ease joint pain from rheumatoid arthritis or reduce bowel inflammation in Crohn’s. That’s why seeing a rheumatologist isn’t optional-it’s essential. When eye and immune health are treated together, outcomes improve dramatically. The days of siloed care are over. The future is integrated.

Can autoimmune uveitis cause permanent vision loss?

Yes, if left untreated or poorly managed. Chronic inflammation can lead to cataracts, glaucoma, macular edema, retinal detachment, or optic nerve damage-all of which can cause irreversible vision loss. Early diagnosis and consistent treatment are critical to prevent these outcomes.

Is Humira the only FDA-approved drug for autoimmune uveitis?

As of 2025, Humira (adalimumab) is the only biologic specifically approved by the FDA for non-infectious uveitis. However, other TNF inhibitors like infliximab and etanercept are widely used off-label and supported by clinical evidence. More drugs are in trials, and approvals are expected in the coming years.

How long does it take for steroid-sparing drugs to work?

It varies. Methotrexate and cyclosporine can take 6 to 12 weeks to show full effect. Biologics like Humira often start working in 2 to 6 weeks. Steroid reduction usually begins after the first few months, once inflammation is under control. Patience and monitoring are key-these drugs aren’t instant fixes.

Can I stop all steroids once I start steroid-sparing therapy?

Many patients can reduce or stop steroids entirely, but not always immediately. Doctors taper steroids slowly to avoid rebound inflammation. Some people need a low dose long-term, especially if their uveitis is very active. The goal is the lowest possible dose for the shortest time-never abrupt withdrawal.

Are there natural alternatives to steroid-sparing drugs?

No proven natural alternatives exist for controlling autoimmune uveitis. Supplements like omega-3s or turmeric may support general immune health, but they cannot replace immunosuppressants or biologics. Relying on them instead of medical treatment risks permanent vision damage. Always discuss any supplements with your doctor.

How often do I need eye exams if I’m on steroid-sparing therapy?

Initially, every 2 to 4 weeks to monitor response and side effects. Once stable, every 3 to 6 months. Blood tests for liver, kidney, and blood cell counts are typically done monthly at first, then every 2 to 3 months. Don’t skip these-even if you feel fine. Uveitis can flare silently.

What should I do if I get sick while on immunosuppressants?

Call your doctor immediately. Infections can become serious quickly when your immune system is suppressed. You may need to pause your medication temporarily. Avoid close contact with sick people, get annual flu and pneumonia vaccines (but avoid live vaccines), and practice good hand hygiene.

Aidan McCord-Amasis

Steroids gave me moon face for 6 months. 🤡 Glad there’s finally a way out. Humira saved my vision and my self-esteem.

Katie Baker

This is the most helpful post I’ve read in years. I’ve been scared to ask my doc about switching from prednisone. Now I know what to say. Thank you.

Jennifer Walton

The body is not a machine. It’s a negotiation. Steroids are coercion. Biologics are diplomacy.

Kihya Beitz

So let me get this straight… we’re giving people cancer drugs to fix their eyes? And you call that progress? 😂

Adam Dille

I’ve been on Humira for 2 years. My uveitis is quiet. My joints? Better. My mood? Way less zombie-like. Still get infections, but I’ll take it. 🙏

Edward Ward

I’ve been following the literature since 2018, and the shift from broad immunosuppression to targeted cytokine blockade is genuinely revolutionary. The TNF-alpha inhibitors were the first real foothold, but IL-17 and JAK inhibitors are where the real precision medicine is emerging-especially in pediatric cases where the inflammatory cascade is more dynamic. The data from UT Southwestern is particularly compelling, not just for efficacy but for long-term safety profiles. We’re moving from symptom suppression to pathway modulation, and that’s not just medical progress-it’s philosophical.

John Foster

They told me I’d be on steroids forever. Then they told me Humira was "off-label" for my Crohn’s uveitis. Then they told me it was "experimental." Meanwhile, my vision kept fading. Now I’m on it. And guess what? The system didn’t care until I started bleeding from the eyes. This isn’t medicine. It’s a lottery.

Jessica Chambers

I got my first blood test result back yesterday. My liver enzymes are up. My doctor says "it’s fine, we’ll monitor." Meanwhile, I’m Googling "can you die from methotrexate?" 🤭

Jonathan Dobey

Let’s be real: Big Pharma wrote this entire guideline. They don’t care if you see. They care if you keep buying. Humira costs $70,000 a year. Who’s getting rich? Not you. Not me. The system is rigged. And the "clinical trials"? Sponsored by the same companies selling the drugs. Wake up.

Chris Bryan

I’m not anti-science. I’m pro-common-sense. Why are we injecting people with synthetic proteins when we could fix their gut? I’ve seen 12 people with uveitis. All of them had leaky gut. All of them ate gluten. All of them were told to take a pill. The truth is buried under jargon.

BABA SABKA

Biologics are just fancy immunosuppressants. You're not curing anything-you're just silencing the alarm. The immune system doesn't "go rogue"-it's screaming because something’s broken. Fix the root. Not the symptom. That’s what real medicine does.

Shyamal Spadoni

You know what else causes uveitis? 5G towers. And glyphosate. And the CDC hiding the truth. They don’t want you to know that natural sunlight and turmeric cure this. They need you on Humira so they can track your biometrics. The eye is the window to the soul-and also the window to your data. Check your HLA-B27 results. They’re fake. It’s all a psyop.

Ogonna Igbo

In Nigeria we don’t have Humira. We have prednisone and prayer. If you can’t afford the drug, you’re not sick-you’re just unlucky. This whole system is built for rich countries. We die quietly. You write long posts. That’s the difference.

Andrew Eppich

It is imperative to emphasize that the utilization of biologic agents in the management of non-infectious uveitis remains, at its core, an off-label application in most contexts. While the FDA has granted approval for adalimumab, the broader therapeutic landscape is still governed by consensus guidelines rather than robust, long-term, randomized controlled trials. To suggest that these treatments are "game-changing" is, frankly, premature. One must exercise caution, not enthusiasm, in the face of such complex immunomodulatory interventions.