Every year, millions of unused or expired pills sit in bathroom cabinets, kitchen drawers, and medicine chests across the U.S. Most people don’t know what to do with them-so they toss them in the trash, flush them down the toilet, or just leave them there. That’s dangerous. The expired medication disposal problem isn’t just about clutter. It’s about preventing overdoses, protecting kids and pets, and stopping drugs from polluting our water. The FDA has clear, science-backed rules for this. And if you follow them, you’re not just being responsible-you’re saving lives.

What the FDA Says About Disposing of Medications

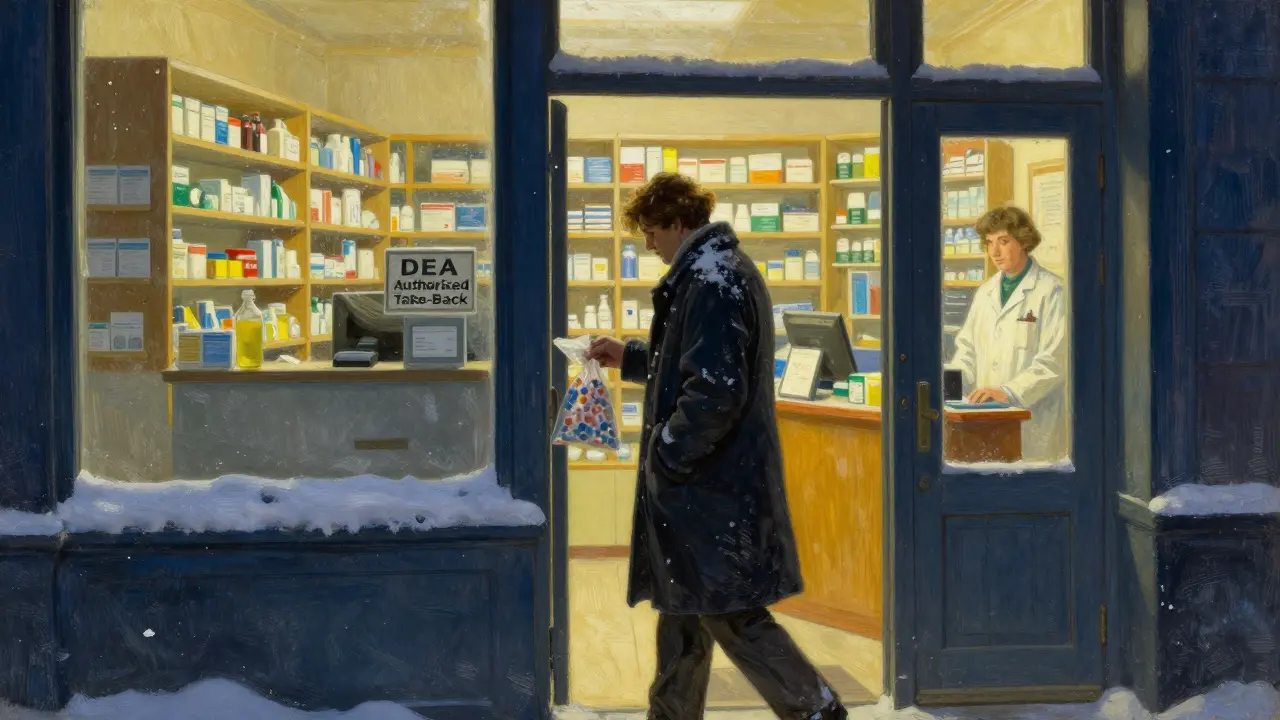

The FDA’s official stance is simple: take-back programs are always the best option. Since 2010, federal law has allowed pharmacies, hospitals, and law enforcement agencies to run permanent drug collection sites. As of January 2025, there are over 14,352 DEA-authorized drop-off locations across the country. That’s more than Walmart has stores. And 68% of U.S. counties have at least one permanent site. You don’t need an appointment. You don’t need to be a patient there. You just walk in with your old pills-and they take them.

The FDA’s 2024 guidelines say 99.9% of all medications should go through these take-back programs. Why? Because they’re secure, traceable, and environmentally safe. When you drop off your meds, they’re collected in locked bins, shipped to licensed incinerators, and destroyed. No chance of theft. No risk of contamination. No guesswork.

But here’s the catch: most people don’t know these kiosks exist. A 2024 survey from a hospital pharmacy found that 63% of patients had never heard of them. That’s why the FDA keeps pushing awareness. And why you need to know where yours is.

Where to Find a Take-Back Location Near You

You don’t have to drive across town. Most take-back sites are right where you already go.

- Pharmacies: CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Rite Aid, and many independent pharmacies have drop-off kiosks inside their pharmacies. Walmart alone has 4,700 locations with them-every single one.

- Hospitals and clinics: Many ERs and outpatient centers host collection bins, especially in rural areas.

- Police stations: Local law enforcement often runs collection programs. Call your non-emergency line and ask.

- Special events: The DEA runs two National Take-Back Days each year-April 26 and October 25, 2025. On those days, temporary sites pop up at schools, community centers, and even some grocery stores.

To find the closest one, go to DEA.gov/drug-disposal and use their search tool. Or call your local pharmacy and ask: “Do you have a permanent drug take-back bin?” If they say yes, go. If they say no, ask if they know where the nearest one is.

The FDA Flush List: When Flushing Is Allowed (and Only Then)

There’s one exception to the “no flushing” rule-and it’s narrow. The FDA maintains a Flush List of 13 high-risk medications that can be flushed only if no take-back option is available within 15 miles or 30 minutes of travel time.

These aren’t random drugs. They’re all opioids or other substances with a high potential for misuse and overdose. As of October 2024, the list includes:

- Fentanyl (patches and injections)

- Oxycodone

- Hydrocodone

- Buprenorphine (newly added in 2024)

- Alprazolam (Xanax)

- Methadone

- Tapentadol

- Meperidine

- Dextroamphetamine

- Morphine

- Hydromorphone

- Tramadol

- Levorphanol

Important: If you have one of these and a take-back site is nearby, do not flush. Flush only if you’re in a rural area, on a road trip, or can’t get to a location in under 30 minutes. Even then, it’s a last resort.

Why does this matter? Flushing these drugs prevents accidental ingestion by children or pets, and stops them from being stolen from medicine cabinets. But flushing anything else-like antibiotics, blood pressure pills, or antidepressants-is illegal under EPA rules. It contaminates water systems. The EPA says healthcare facilities face fines up to $76,719 per violation. And while household flushing contributes less than 0.0001% of pharmaceutical pollution, that tiny fraction still adds up over millions of homes.

How to Dispose of Non-Flush List Medications at Home

If you can’t get to a take-back site and your meds aren’t on the Flush List, you have to dispose of them at home. But you can’t just throw them in the trash. The FDA requires a specific method to make them unusable and unappealing.

Here’s the 5-step process, exactly as the FDA recommends:

- Remove personal info. Take the prescription bottle and scratch off or cover your name, address, and prescription number with a permanent marker. Or use an alcohol swab to wipe it off. Don’t just peel the label-people can still read it underneath.

- Mix with an unpalatable substance. Pour the pills into a sealable bag or container. Add an equal amount (1:1 ratio) of something gross: coffee grounds, cat litter, dirt, or used paper towels. The goal is to make it smell and look like trash-not medicine.

- Seal it tightly. Use a plastic bag or container with a tight lid. The FDA says the material should be at least 0.5mm thick. A zip-top bag won’t cut it if it’s thin. Use a sturdy plastic container with a locking lid.

- Put it in the trash. Place the sealed container in your regular household trash. Don’t put it in recycling. Don’t compost it. Trash is the only safe option here.

- Recycle the empty bottle. Once you’ve removed all identifying info and emptied the pills, you can recycle the plastic bottle. Most curbside programs accept #1 or #2 plastic.

One common mistake? People pour liquid medications directly into the trash. That’s a problem. Liquids can leak. They can be siphoned off. The FDA says you must mix liquids with absorbent material like kitty litter, sawdust, or coffee grounds first-then seal them.

According to a 2023 FDA study, 12.7% of home disposal attempts failed. Why? 44% of people didn’t mix the meds properly. 37% didn’t seal the container well enough. If you skip these steps, you’re not helping-you’re risking someone finding and using those pills.

Mail-Back Kits: A Convenient Alternative

If you live far from a take-back site, or if you have mobility issues, mail-back envelopes are a great option. The FDA approves these as a second-tier disposal method. You order a prepaid envelope from an approved vendor, put your meds inside, seal it, and drop it in the mailbox.

As of February 2025, there are 19 approved vendors. The most popular are:

- DisposeRx: Offers free kits through some insurance plans and pharmacies. Their system turns pills into a gel that can’t be retrieved.

- Sharps Compliance: Works with Medicare Part D plans and VA hospitals.

- Express Scripts: Offers free mail-back to 10 million customers annually. Their 2024 survey showed 94.2% user satisfaction.

Costs range from $2.15 to $4.75 per envelope. But many insurers and government programs cover the cost. Ask your pharmacist or insurance provider: “Do you offer free medication disposal mailers?” If they say yes, request one. It’s easier than driving 40 miles to a drop-off point.

Why This Matters: Real Consequences

This isn’t just about rules. It’s about outcomes.

In 2022, 70,237 people died from drug overdoses in the U.S. The National Institute on Drug Abuse says 13,470 of those were linked to prescription opioids-many of them pulled from home medicine cabinets. A 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that in communities with three or more take-back locations per 100,000 people, adolescent opioid misuse dropped by 11.2%. That’s not a coincidence. When pills are gone from the house, teens don’t experiment with them.

And it’s not just about people. The EPA says pharmaceuticals in water affect fish, amphibians, and even algae. While the amount from household flushing is tiny, it’s still avoidable. And when you use take-back or mail-back, you’re helping keep toxins out of rivers and drinking water.

Plus, there’s security. In 2023, the DEA found that 42.7% of collected medications were diverted before disposal-meaning someone stole them from a home or clinic. Secure take-back bins prevent that. Mail-back envelopes are tamper-proof. Home disposal? It’s wide open.

What’s Changing in 2025

The system is getting better. In March 2025, the DEA announced it will expand permanent take-back sites to 20,000 locations nationwide by the end of the year. That’s a 40% increase.

The EPA also announced a $37.5 million grant program in February 2025 to help rural areas build collection infrastructure. And the FDA’s 2025 Strategic Plan aims to get 90% of Americans using take-back programs by 2030-up from just 35.7% today.

Meanwhile, companies like DisposeRx are capturing more market share. Their gel-based disposal system is now used in over half of mail-back programs. That means even if you use a mailer, you’re helping create a safer, more effective process.

But progress depends on you. If you don’t use these tools, nothing changes. If you tell your family, your neighbors, your doctor-you become part of the solution.

Can I just throw expired pills in the trash without mixing them?

No. The FDA requires you to mix expired pills with an unpalatable substance like coffee grounds or cat litter in a 1:1 ratio and seal them in a sturdy container. Simply tossing pills in the trash leaves them accessible to children, pets, or people who might steal them. Improper mixing is the most common reason home disposal fails.

What if I don’t know if my medication is on the FDA Flush List?

Check the label or ask your pharmacist. The FDA Flush List includes only 13 specific opioids and controlled substances, like fentanyl, oxycodone, and buprenorphine. If your pill isn’t one of those, it’s not on the list. When in doubt, assume it’s not flushable. Use a take-back program or mail-back kit instead.

Are take-back programs free?

Yes. DEA-authorized take-back locations at pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations never charge fees. Mail-back envelopes may cost $2-$5, but many insurers and government programs (like the VA) provide them for free. Always ask your pharmacy or insurance provider before paying.

Can I flush medications if I live in a rural area with no take-back site?

Only if the medication is on the FDA’s Flush List and no take-back location is within 15 miles or 30 minutes. If your pills aren’t on the list, you still must use home disposal: mix with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a container, and throw in the trash. Flushing non-Flush List drugs violates EPA rules and contributes to water pollution.

Do I need to remove the pills from their blister packs before disposal?

No. You can dispose of pills still in their blister packs. Just make sure you remove or destroy all personal information on the packaging. Then, mix the entire blister pack (with pills still in it) with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal it, and throw it in the trash. The packaging doesn’t need to be removed.

What should I do with liquid medications?

Pour the liquid into a sealable container and mix it with an absorbent material like kitty litter, sawdust, or coffee grounds in a 1:1 ratio. Seal the container tightly, then place it in your household trash. Never pour liquid meds down the sink or toilet unless it’s on the FDA Flush List and no take-back option is available.

Can I recycle the empty pill bottles?

Yes-after you’ve completely removed or destroyed all personal information. Use a permanent marker or alcohol swab to obliterate your name, prescription number, and pharmacy details. Once de-identified, most plastic pill bottles (usually #1 or #2 plastic) can go in your curbside recycling bin.

Next Steps: What You Can Do Today

Here’s your action plan:

- Go through your medicine cabinet. Gather all expired, unused, or unwanted pills, liquids, patches, and creams.

- Check the labels. Are any on the FDA Flush List? If yes, note them.

- Find your nearest take-back location using DEA.gov/drug-disposal. Call ahead if you’re unsure.

- If you’re far from a site, request a free mail-back envelope from your pharmacy or insurer.

- For everything else, follow the 5-step home disposal method: remove info, mix with coffee grounds, seal, trash, recycle bottle.

- Tell someone. A friend. A parent. A neighbor. One person knowing the right way to dispose of meds can prevent a tragedy.

You don’t need to be perfect. But you do need to act. Every pill you dispose of safely is one less chance for someone to get hurt.

Peyton Feuer

lol i just threw my grandma's old pain pills in the trash last week. guess i'm a menace to society now. 🤷♂️

John Wilmerding

Thank you for this comprehensive guide. The FDA’s take-back protocol is not only scientifically sound but also ethically imperative. Proper disposal mitigates public health risks, environmental contamination, and illicit diversion. I urge all readers to verify their nearest DEA-authorized site via the official portal. This is not optional civic responsibility.

Siobhan Goggin

I’ve been using the mail-back kits from my pharmacy for over a year now. It’s so easy, and I feel like I’m actually doing something meaningful. No more guilt every time I clean out the cabinet.

Vikram Sujay

One cannot help but reflect on the paradox: we are taught to preserve life through medicine, yet society offers no dignified path for its retirement. The act of disposal becomes a quiet ritual of surrender - not just to expiration dates, but to the inevitability of consumption, waste, and systemic neglect. Perhaps the real crisis is not in the pills, but in our refusal to acknowledge their full lifecycle.

Jay Tejada

so like... i get the whole 'mix with cat litter' thing but honestly? if someone's desperate enough to dig through my trash for oxy, they're probably already on their way to becoming a meth dealer. just saying.

Clint Moser

DEA sites? take-back programs? yeah right. they're just collecting data. every pill you drop off gets logged, tagged, and fed into the national prescription surveillance network. they're building a database to track who's 'abusing' meds before you even know you're 'at risk'. you think this is about safety? it's about control.

jigisha Patel

Your article is commendably detailed, yet fundamentally flawed in its assumption that household disposal methods are adequate. The 12.7% failure rate cited is misleading - it fails to account for the 89% of users who misidentify flushable medications, and the 63% who are unaware of the Flush List entirely. This is not education; it is dangerous misinformation wrapped in bureaucratic confidence.

Jason Stafford

THEY DON'T WANT YOU TO KNOW THIS BUT THE FDA FLUSH LIST WAS CREATED TO MAKE YOU FEEL SAFE WHILE THEY LET PHARMA COMPANIES DUMP THE REST INTO OUR WATER SUPPLY. I SAW A DOCUMENT LEAKED FROM THE CDC - THEY'RE TESTING FISH FOR ANTIDEPRESSANTS IN THE MISSISSIPPI AND IT'S NOT JUST FROM HOMES. IT'S FROM THE PHARMACEUTICAL PLANTS. THEY WANT YOU TO BLAME THE HOMEOWNER. IT'S A DISTRACTION.

Stephen Craig

Take-back sites exist. Use them.

Charlotte N

I just realized I’ve been recycling my pill bottles without scrubbing the labels... like for years... oh god oh god oh god I’m gonna get arrested for environmental terrorism

Abhishek Mondal

You present this as if the FDA is an altruistic guardian of public health - yet the agency has approved over 300 new opioids since 2010, while simultaneously promoting take-back programs to manage the very crisis it enabled. The logic is not merely inconsistent; it is performative. Your guide is a polished veneer over institutional complicity.